Dries Van Noten

“I think the pandemic really ignited that belief that if we don’t try to change something now, we never will change.

Dries Van Noten On Len Lye, Gardening & Reforming The Fashion System

The revered Belgian fashion designer talks about tripping out on New Zealand artist Len Lye and how he's adapted to fashion's changing tides. | By Dan Ahwa, Viva Magazine - Volume Two, Summer 2020/2021.

'In the end, everything is just the same’ is the English translation of the Samoan term ‘Tusalava’, and the name of artist Leonard Charles Huia Lye’s pioneering experimental film that premiered at the London Film Society in 1929.

The animated black and white film painstakingly created with 4400 individual drawings is one of Lye’s most prolific works and showcases the progressive mind of one of Aotearoa’s beloved art figures. It’s moving imagery at its most primitive, yet still modern 90 years later.

For Dries Van Noten, Belgian fashion designer and alum of the influential collective ‘Antwerp Six’, it’s a world not far removed from his own passion for print, colour and movement.

Despite living in entirely different decades — Lye died in 1980 just as Dries graduated from Antwerp’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts — their progressive kindred spirits were connected earlier this year via the internet.

“I Googled him!” laughs Dries, the 62-year-old beaming via Zoom from his elegant Antwerp office. “I knew I wanted to focus on colour, lightness and movement. When I was researching related ideas online, Len’s name would pop up often and so we looked deeper into his work and found it was exactly the mood we wanted to convey.”

Framed by a backdrop of vintage oak cupboards inherited from the local courthouse, Dries — once described by The New York Times as “one of fashion’s most cerebral designers” — is simultaneously elegant and candidly frank when talking about his work — specifically his new spring/summer 2021 collection released during the lockdown in October.

“I didn’t know much about him, and in fact your fellow countryman Tim Blanks (Business of Fashion’s editor-at-large) who is knowledgeable in contemporary art, even asked me ‘who is that?’” Dries says laughing. “Len is quite obscure — he touched so many different things. He knew so many different people and lived in so many different cities and yet at the end, he’s not so well known. Yet you can feel the quality, how modern and forward-thinking he was.”

Len Lye (Performance With Petals), 1970 courtesy of Len Lye Foundation Collection, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery

The unique connection to the Christchurch-born artist’s work — arguably one of the most original thinkers in 20th-century art — feels natural. Lye’s exploration of movement, colour and light is not far removed from Dries’ own appreciation for bold colours, clashing prints and rich embroidery. His concept-driven designs have referenced everything and everyone from the macabre and emotive world of artist Francis Bacon to the glamour of Ziggy Stardust.

Lightness, freshness and colour proved fundamental starting points for the designer and his team, who worked closely with the Len Lye Foundation in New Plymouth, with support from specialists at Ngā Taonga and the Govett Brewster Art Gallery/Len Lye Centre.

“Once we saw Len’s films, my first thought was these originated from the 1960s psychedelic movement. But it was quite strange when you see the films and hear this kind of Josephine Baker type of music. You quickly realise it’s not the 60s, it’s actually the 30s. I thought ‘Wow, this is really amazing’.”

Trust is also a key component of working remotely these days, and the 18,000km between Antwerp and New Plymouth required flexibility and patience between both camps in order for Dries to be fully immersed not only in the work itself, but in Lye’s way of thinking.

“It would be a little sad just to say, ‘Okay, this image is nice, let’s replicate it on fabric’,” says Dries. “It really was about the whole idea of Len’s mind, the craft of how he created prints directly on the celluloid — that scratching, stencilling and painting on the film for me was so important.

“Of course, when you work, you make mock-ups, you make try-outs, you see what’s working, what’s not working. So it’s really something that develops and grows.

“We were allowed also to make different colour combinations — but still respecting his way of putting colours together and the overall atmosphere. The Foundation provided us with plenty of support, information and flexibility, which was a true collaboration.”

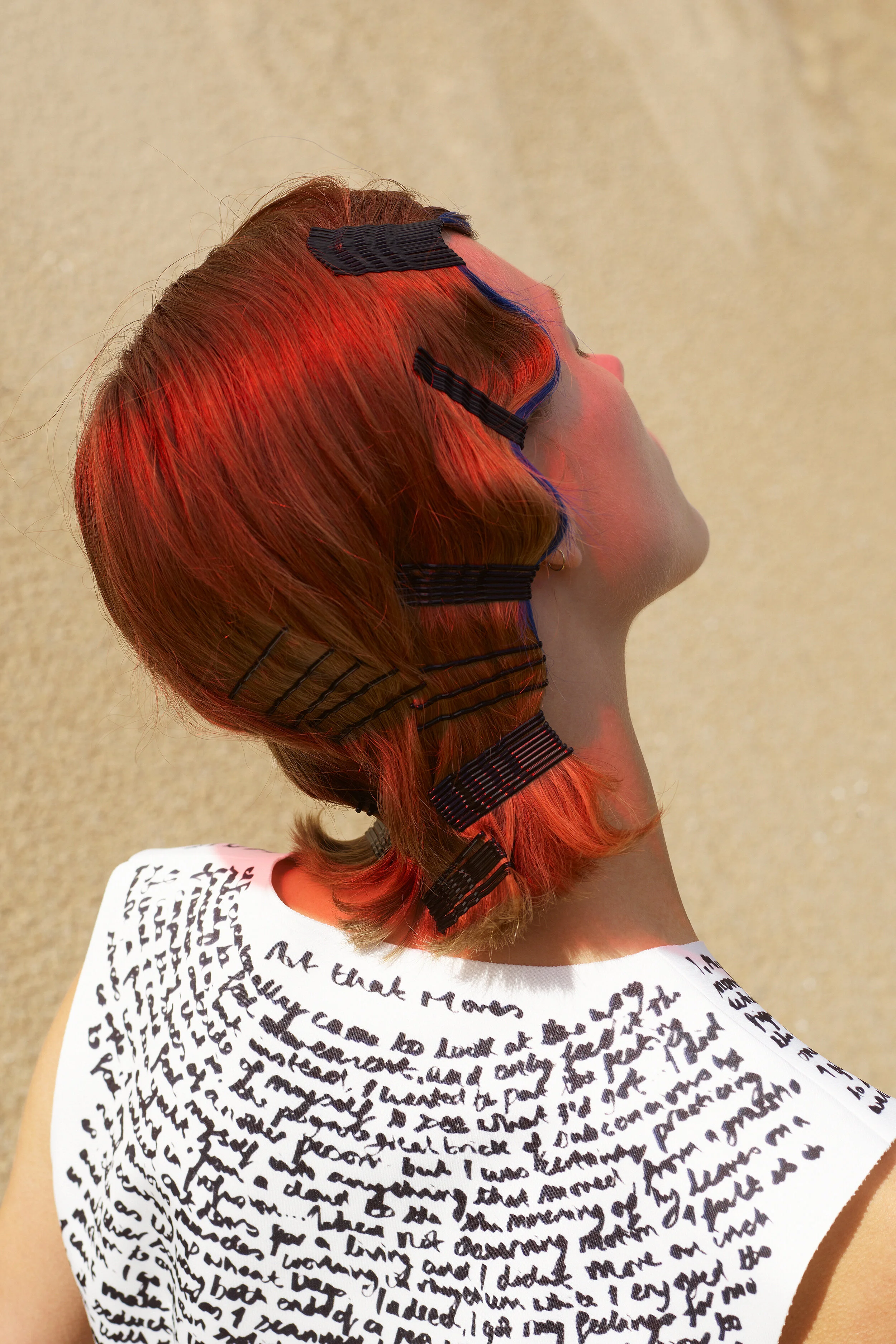

Amalgamating both his menswear and womenswear collections as a digital presentation for the first time in Dries’ 34-year career, the collection’s accompanying photos and film were shot by Dutch photographer Viviane Sassen on Rotterdam Beach and in studio, to better showcase Lye’s art projected onto models’ faces and garments.

Len Lye’s ‘Art That Moves’ manifesto rendered on the back of a Dries Van Noten dress. Photo / Viviane Sassen

“There is one dress that features a manifesto from Len about movement entitled ‘art that moves’, which was completely handwritten on the dress.”

Such creative freedom is a rarity in a world filled with clothes designed by marketing teams, and while no longer privately owned — the Dries Van Noten company sold a majority stake of the business to Spanish group Puig in 2018 — the purity of design is even more pronounced in collections such as this.

“I wanted to have a future for the company, but I think we proved that it can be also a different way. Even when you’re not privately owned, you can still be a very creative company and do very unexpected things — even in the middle of a pandemic.”

Case in point: the brand opened its first concept store in LA in the former heritage building once occupied by Opening Ceremony on La Cienega Boulevard and, in May, Dries released an open letter to the fashion industry calling for a fundamental reassessment of its operations.

“I think the pandemic really ignited that belief that if we don’t try to change something now, we never will change. Fashion became a rat race. The bigger groups started to add more product. Designers had to have dresses ready for delivery in November and winter coats in May — which was complete madness.”

To counter-balance his work life, Dries' well-documented passion for his garden offers him plenty of inspiration and respite from running a successful business, his description of the garden's current state typically poetic.

"The garden at the moment is looking great coming to the end of autumn here. For the first time we started getting night-frosts this morning and it was really beautiful because we had the white shimmer over the garden. And we still have a lot of brightly colored leaves on the trees — so the combination of this frost with the bright colors looks really great for the moment."

"I just gave the gardener a long list of things that I want to add, and yesterday morning I decided to plant more tulip bulbs because it's about now when we need to start planting these for fresh flowers come spring."

"I love tulips in the morning. We don't plant them the flower beds, but we plant some just in rows just so we can have them for the house and to bring it to the office and to share with friends. And I think it's, it's really nice being that in the spring when people come they can go home with the arm full of big tulips. I love seeing the cycle of nature this way."

For his local fans who might find pieces from long-time stockists Scotties or Zambesi, there’s a universal language and appreciation for his designs that Dries simply puts down to creating garments — like Lye’s approach to his art — that does not date.

“What we try to do is create clothes that can live long lives. We try to tell a story, but afterwards I forget the story and I design clothes one by one. I really try to ensure every garment has a reason of being.

“What we hear quite often is people sometimes put garments away for a couple of years, and they rediscover these and wear them again. And this makes me always happy.”

– Originally published in Viva Magazine – Volume Two